The Great Escape

PREFACE

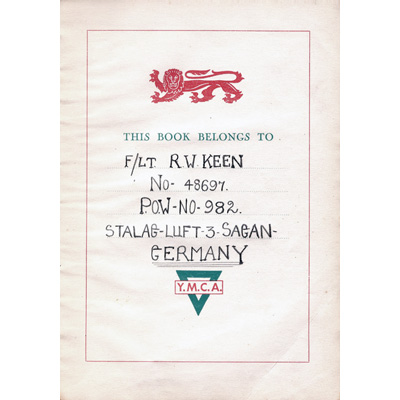

Over the years the story of the Great Escape has been told and retold many times, and with numerous revisions. The collectively sourced details below are from some of the earliest accounts, including Private Editions from as early as 1946. Interspersed are quotations from The Tunnel written by F/Lt Raymond Keen who as a POW in the North Compound and a participant in the building of the tunnel, captured the events of that night in a poetical narrative. This narrative may indeed represent one of the first, if not the first chronicling of the Great Escape story by an eyewitness.

WELCOME TO STALAG LUFT III

Opened in March of 1942 in the German province of Silesia, Stalag Luft III, or Stammlager Luft III to give it its proper German title, was built as a POW camp for Allied airmen. Administered by the Luftwaffe, the man in charge was a decorated World War I veteran, Kommandant Oberst (Colonel) Friedrich von Lindeiner-Wildau. The camp began life as a single enclosure, known as the East Compound, which was soon joined by a second, the Center Compound. A year later on 29 March 1943, a further was added. This was the North Compound and events within its barbed-wire would become immortalized in military history.

The North Compound consisted of fifteen wooden huts, each one divided into sixteen rooms which housed around eight men, plus three sets of private quarters for senior officers. The compound itself was a square of about a 1000 feet in both directions, hemmed in by two layers of barbed-wire and guard towers positioned at regular intervals. Armed guards manned the towers night and day, and patrols continuously circled the perimeter. A warning wire ran close to the inner fence. The prisoners were warned not to stray beyond that wire under threat of death. A system of seismographic microphones also ringed the compound, specifically designed to detect tunneling activity. At the northern end was the vorlager area, a separate enclosure which contained the compound’s medical quarters and notorious cooler, an isolation block for errant prisoners. Thick pine forests flanked all sides of the camp. The only other evidence of civilization was a small road which ran off toward the nearby town of Sagan (Żagań).

Eventually, the camp had six compounds, with the additional South, West and annexed site Balaria, holding a mixture of mostly US and Commonwealth airmen.

The camp was officially called Stalag Luft 3 by the German authorities, and it was only through the influence of subsequent literature, such as Paul Brickhill’s The Great Escape, that it has come to be more popularly known as ‘III’.

Map of the North Compound

A NEW ARRIVAL

Less than two weeks after its opening, F/Lt Raymond Keen of the RAF’s 78 Bomber Squadron arrived in the North Compound of Stalag Luft III. His aircraft, a Halifax II (W7931), had been shot down following a nighttime raid on Duisburg. After having spent the previous few days being interrogated at Dulag-Luft, a transit camp for captured airmen run by the Luftwaffe, the welcome he received in Stalag Luft III was not quite what he was expecting. Once more he found himself grilled, though this time by a select group of existing POWs. Furthermore, these same men seemed to take more than a passing interest in his movements there. In due course, he would find out why.

F/Lt Keen's Wartime Log

THE MAIN CHARACTERS

- Squadron Leader Roger Bushell

- Kommandant Friedrich von Lindeiner

- Group Captain Herbert Massey

- SS-Gruppenführer Arthur Nebe

THE TUNNELS

We already know as what ensued became the stuff of legend. In late March a secret meeting had taken place in one of the huts. Squadron Leader Roger Bushell, a downed Spitfire pilot who was head of the camp’s escape committee, called the X Organization, addressed the members present.

“Everyone here in this room is living on borrowed time. By rights, we should all be dead! The only reason that God allowed us this extra ration of life is so we can make life hell for the Hun. In North Compound we are concentrating our efforts on completing and escaping through one master tunnel. No private-enterprise tunnels allowed. Three bloody deep, bloody long tunnels will be dug – Tom, Dick, and Harry. One will succeed!”

S/L Roger Bushell

The camp already had a prolific history of escape attempts, the most famous up til then being the Wooden Horse endeavor in October of 1943. However, the digging of three simultaneous tunnels would be taking matters to an entirely different level. If those listening were left stunned by the audacity of the plan, then they would have been even more so on learning the number of escapees Bushell intended. Over two hundred men. The plan was unanimously agreed upon, and with the consent of the camp’s Senior British Officer, G/C Herbert Massey, Bushell or Big X as he was known within the organization, began the practical tasks of bringing his vision to fruition.

Hut 104 was selected as the gateway for Harry. A stove was slid aside and a section of tile beneath carefully taken up and set into a concrete tray which created a detachable trapdoor. The stove was returned into place and then only moved to allow access to the work below. In the months that followed, the hut was searched on numerous occasions, but the guards never came close to uncovering the cleverly disguised portal. Tom, which was located in Hut 123, similarly had its entrance concealed by a stove while Dick utilized a drain in the shower room as its starting point, Hut 122. F/Lt Keen was quartered in Hut 122 with fellow so-called Kriegies from England, South Africa, and Australia. The term Kriegies originated from the German kriegsgefangener, meaning prisoner of war. Tunnels Tom and Dick ran in the same westerly direction, and it was conceived that, if necessary, they may be joined at some point.

Diagram of Tunnel Harry

The next step was to dig shafts sufficiently deep to avoid the regular probing patrols of the ferrets, the nickname given to a section of the camp guards specifically engaged in escape detection. The most dreaded among these was a character known as Rubberneck, Unteroffizier Karl Griese, who had developed a reputation as the most wiley and formidable of that specialist team. The measurement decided on was thirty feet (9 m), and so inch by inch, foot by foot, the men dug down into the sandy earth beneath each hut until the required safe depth had been reached. The shafts, like the tunnels that followed, were shored up by wooden slats commandeered from the POW’s bunks.

At the foot of each shaft, the men excavated pump rooms in which they installed bellows style air pumps which had been built in secret and smuggled down into the tunnels. Drawing from a disused chimney above, in Harry’s case, the contraptions supplied ventilation along pipelines imaginatively strung together from old Klim (Red Cross powdered milk) tins.

Down in that same area, the men added workshop spaces which were used for building the timber supports for the tunnel, as well as the wooden tracks and trolleys of rudimentary railways. Running on flanged wheels, these carts were designed to get men, tools, and debris back and forth along the tunnel in a fraction of the time it would take to crawl. In Harry’s instance, the railway system eventually comprised three sections, and passengers had to swap trolleys twice to complete the full journey. In a touch of humor, these swap over points were named after London Underground stations, Piccadilly Circus and Leicester Square.

The tunnels were narrow, barely 2 feet (0.6 m) square and prone to collapse, providing a claustrophobic and hazardous working environment. Many of the men chose to toil naked, unencumbered by clothing which would have made navigation more arduous. Makeshift showers were rigged up in the washrooms so that they could quickly rid themselves of the telltale signs of their labors. The average daily progress on each tunnel was a formidable seven to eight feet.

The work below was divided into two shifts. The first was the actual digging, which usually took place between morning appell (9.30 a.m.) and evening appell (around 5.30 p.m). The second shift which went on into the night concentrated on the disposal of the earth excavated that day.

At this stage, the North Compound still held a contingent of US airmen who were actively involved in the escape efforts. Men such as Lt/Col Albert Clark (31st Fighter Group), Big S as he was known, who was in charge of the security team, the Stooges. Their role was to monitor the movements of the goons, a nickname applied to the ordinary camp guards, and the Germans and that somewhat more dangerous faction among them, the ferrets.

Disposing of the sand was one of the biggest difficulties attached to the project. F/Lt Keen, having by this time won the trust of those in the Escape Committee, was one of many in the colony of Penguins who on a daily basis would potter around the compound with makeshift bags full of sand stashed inside their pants. Picking their moments, usually when passing the vegetable gardens where the earth was fresh, the men would release small amounts of debris using a drawstring and inconspicuously trampling it in. It is estimated that at least 25,000 of these ingenious disposal trips were made during Harry’s construction. At times when snow covered the ground, this method became impossible so that the sand would be stashed beneath the camp theater.

Another group of POWs, known as the Y Organization, were also busily at work. They were responsible for the forging of documents and maps, as well as serving as the general quartermaster for all items required by the escapees, from clothing through to food rations. Among their number were former tailors and artists whose skills were invaluable, providing as much authenticity as possible to the false identities of the men who would escape. Then there was the Z Organization. This was the most secret branch of the triad. They had control over the camp’s illegal radio and were versed in the codes which allowed them to communicate with RAF Intelligence back in England.

In June, it was announced that Clark and all the other U.S. airmen would soon be moved into a new enclosure, the South Compound, which was nearing completion. At this point, tunnel Tom had already reached beyond the wire and efforts continued apace to finish it ahead of the move so that the U.S. airmen could still take part in the escape. Work was suspended on Harry and Dick so that all manpower could be focused on getting Tom ready in time. They had only six weeks. However, in the midst of this concerted push, the Germans began to clear the woods for yet another new compound. As luck would have it, its location was right in the path of Tom. This meant that additional fifty yards of digging would be required to still surface within the cover of the woods.

Chief of the ferrets, Oberfeldwebel Glemnitz, aware that the summer months were traditionally prime escaping time, intensified the daily search and surveillance efforts of his men. This eventually paid off when a guard found some of the disposed sand in one of the gardens, which lead to scrutiny being ramped up even further. A game of cat and mouse ensued between the POWs and the goons, which finally ended when a guard, probing with a metal spike, discovered the entrance to Tom. The Germans then closed the tunnel permanently using an explosive charge.

In late August, the American airmen were indeed transferred to their new compound, effectively curtailing their involvement in the escape efforts. Ironically, as history would later testify, the event probably also saved many an American life.

The incident with Tom had put the Germans on alert. It was decided to pause tunneling activity on Harry and Dick, at least until things settled down. It was not until January of the following year that digging would resume. After some debate, it was agreed that Harry was the only viable tunnel left as the new compound which helped thwart Tom also lay in Dick’s path. Not only that but in haste to fully complete one tunnel, Dick had been sacrificed to some degree and filled with earth from Tom.

The work underground was given a much-needed boost when one resourceful Canadian officer, Joe Red Noble, pilfered about 600 feet of electric cable from local workmen. This was put to good use providing a simple lighting system within Harry. Previously the only light available had come from primitive candles, fueled by margarine with a piece of pajama cord as a wick. However, the improvement did not come without cost. The three Germans responsible for the wire were later shot by the authorities for not disclosing its loss.

It wasn’t long before the Germans interrupted events again by suddenly transferring the men they considered high-risk prisoners to another camp. Among them were some of the key figures in the scheme, such as F/Lt Wally Floody, the chief tunnel executive, and F/Lt George Harsh, the head of security. In spite of this, with their efforts and resources narrowed to just one tunnel, progress was much swifter, and by March they had dug beyond the compound perimeter. Escape was now viable.

As such, there was no fixed date for the crawl to freedom. It was only in the hours preceding the 24 March 1944, that Bushell made the decision to break the tunnel that coming night. A number of factors may have helped influence events. First and foremost, it was a moonless night, and it would be another month before the lunar cycle provided such favorable conditions again. Also, the camp’s evening curfew had recently been relaxed, which allowed the prisoners to move freely around the compound to a later hour. Finally, arch nemesis Rubberneck just happened to be away on leave.

In an interview, Clark later described how Bushell informed him of the news.

“He simply called me out to the wire and said, ‘We go tonight, so don’t do anything tonight that would mess it up.’ We always coordinated our escape attempts between the camps.”

In all, 220 men were chosen to escape. Bushell picked sixty of these, based on their German language skills and previous escape experience. These men were known as the serial offenders. Another 140 were then chosen randomly by drawing lots. They too were given a name, hard-arsers, men who had little chance of completing a “home run” but were still willing. Lastly, twenty more places were awarded to those who had missed out in the draw but were deemed to be most deserving. F/Lt Keen was included in the initial draw, but his name remained in the hat. His role would, therefore, be that of an eyewitness.

THE ESCAPE

After dark, the would-be escapees collected along with others involved in Hut 104. Between them, they had around 400 sets of forged papers, civilian clothes, maps, compasses, ‘iron rations’ (a kind of homemade fudge cake), plus a variety of other gadgets. A hostile country blanketed in deep snow awaited them at the far end of the tunnel. F/Lt Keen watched as events unfolded, sketching out the words of a poem to pass the time.

‘Now comes the time to leave, all are prepared. The leaders by the shaft start to descend, but now his bulky clothing has ensnared him twixt two props near to the tunnel end.’

On reaching the surface, a gut-wrenching sight awaited the first of the would-be escapees. The team’s calculations had fallen some feet short, and instead of emerging within the relative safety of the woods, they came up in open ground just beyond the perimeter of the compound and perilously close to a sentry box.

The news did little to ease the nerves of the waiting men, already anxious and uncomfortable in the heavy wardrobe of clothes they had on in readiness for the harsh conditions once outside. One by one, they descended the shaft and boarded the trolleys to begin their journey to freedom. The first two out were F/Lt Johnny Marshall and Bull. They took with them a rope which reached back into the tunnel and provided a simple means of communication. Bushell and his traveling partner, French pilot LT Bernard Scheidhauer, passed through the tunnel early and took off into the night.

Not surprisingly, the whole process was not without complications. A number of the escapees got themselves stuck in the tunnel due to their bulky clothes and kit. They would require help by those in front or behind. The tight squeeze also caused an actual cave-in, which needed clearing before progress could resume.

‘Hold everything! The air raid sirens wails. Double guards. We can not carry on. God! This is going slower than a snail.’

Suddenly, at around midnight, the air raid sirens began to drone, and the camp fell into a blackout as Allied aircraft were detected over the region. For those in Hut 104, the timing could not have been worse. With the loss of electricity, the tunnel was plunged into total darkness. A period of confusion ensued. Eventually, fat-lamps were passed down into the tunnel and placed at the two main waypoints, providing at least some degree of illumination. Further hindering matters, guard patrols were doubled. It wasn’t long until the huts shuddered with the distant impacts of falling bombs as the aircraft eventually reached their target, Berlin. It is a sober testimony to the destructive forces unleashed by such raids that they could be felt over 100 miles away.

‘Two hours lost, and many who are here will find that they have had their wait in vain. At last the sirens sound the All Clear.’

At 2 a.m. the blackout was finally lifted, and the camp’s electricity was restored. Over the next few hours, progress continued, though with the various delays, the number so far to have escaped was considerably less than expected. As dawn began to break the controllers in Hut 104 decided it was time to call a halt, and dispatched the last three men down the tunnel. 87 men had now made that descent. Meanwhile, up above in the cold, early light, a perimeter guard happened to stray from the regular path and passed right beside the exit hole. At that very moment, confusion with the signals leads to an escapee emerging right behind the sentry. The guard then spotted the trail that had been carved in the snow and followed it back to the man on the ground. At this point, the controller in the woods sprang forth with his hands in the air, attempting to distract the guard. Sounding the alarm with a cry, the sentry fired a warning shot in his direction.

‘A postern sees the footprints in the slush outside the wire, a scuffle a shout. A rifle shot that breaks the morning hush. The break is found, the guards are rushing out.’

The breakout had been discovered. Those few men left in the tunnel beat a hasty retreat back into Hut 104. They immediately set about destroying all evidence they had of involvement in the escape, committing them to ashes in the stove. Outside all hell broke loose. Guards were dashing around with guns in hand, ready to shoot anything that moved. In a state of complete meltdown, the Kommandant was heard to threaten to personally shoot two British officers if there was any further provocation.

‘A fire is made of all escaping kit. Directly they hear sounds of the alert. As fast as one dies out, another lit, and fanned to brighter burning with a slat.’

The Germans began a thorough search of each hut attempting to discover the source of the tunnel. Fortunately for those in Hut 104, they wound up being one of the last in the queue and had sufficient time to erase all evidence and return the environment to something resembling normality. Once the guards had searched to hut to no avail, the Germans pleaded with the adjutant S/L Bill Jennens to disclose the tunnel’s entrance as one of the guards had become trapped in its depth. With the tunnel having served its purpose, Jennens gave up the location, and the stove was removed to reveal the hapless guard, Unteroffizier Charlie Pilz.

Even though less than half of the planned number of escapees had made it beyond the wire, the magnitude of success was considerable. It was the greatest escape of POWs in the history of both World Wars.

The four men who were captured outside the tunnel were immediately sent to the camp’s stockade, known as the cooler. Years later, this isolation block would be enshrined in movie history through Steve McQueen’s character, The Cooler King, in The Great Escape. In the days that followed, others would find themselves guests of the block as the piqued Germans clamped down over the slightest infringement.

‘A later hour, and eighty seven free. Remainder counted, searched and locked indoors.’

THE AFTERMATH

A Grossfahndung (nationwide alert) was declared with all forces, from the Gestapo through to the local police, tasked to locate the men. Of the eighty-seven men who had braved the tunnel that night, four were recaptured immediately outside the compound, and another seven had retreated into Hut 104. Over the coming days, all but three of those who escaped were recaptured, beaten down by the extreme cold and challenges of finding themselves adrift in enemy territory. A number of those with forged papers had intended to make swift headway by rail, but in the darkness, many had struggled to find the local station. Some simply pointed their compasses toward the nearest neutral country and began a futile trek through the frozen wastes. In the confusion of the night and the days that followed, there was some uncertainty over the actual number who had escaped.

Kommandant von Lindeiner was removed from duty and subsequently court-martialed for gross incompetence, though playing on his mental fragility the experienced military veteran managed to escape with only a token sentence. He was replaced by Oberst (Colonel) Braune to whom fell one of the grimmest yet memorable tasks of World War II.

On the morning of 6 April, Massey was summoned before the new Kommandant. Through an interpreter, the German Officer conveyed the somber news that forty-seven of those involved in the break-out had been “shot while trying to escape.” When repeatedly pressed by the shocked Massey on how many of the escapees had only been wounded, Braune reluctantly confirmed, “None.”

The revelation was greeted with dismay and disbelief by those in the North Compound. A few days later, three more names were added to the roll call of the dead. However, many in the camp believed the reports to be false, a scenario manufactured by the Germans to deter any further escape attempts. And indeed, certain actions by the authorities did lend credence to that belief, such as shipping out the possessions of the fifty men which give the impression that they were simply being held elsewhere.

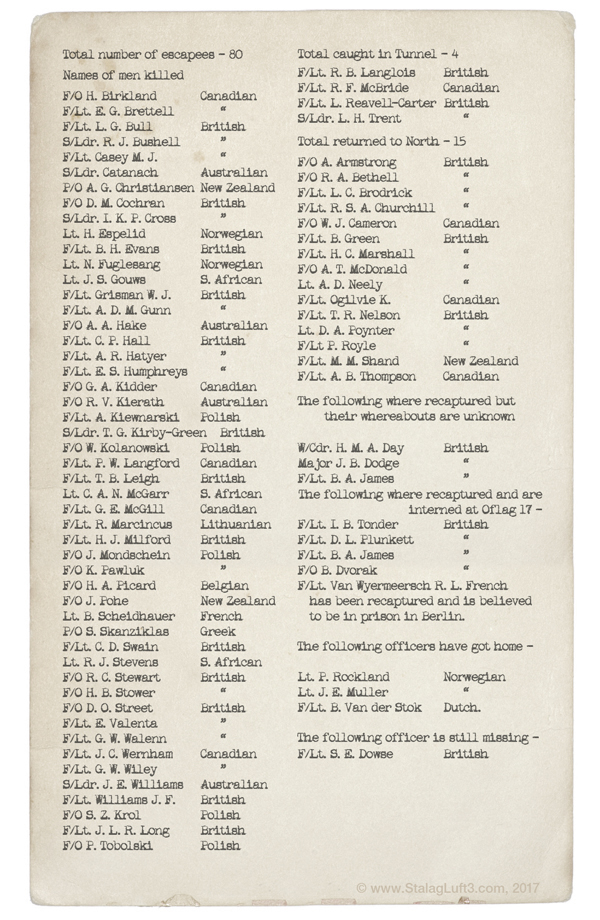

Facsimile of the official list provided by the Senior British Officer in the North Compound accounting for those involved in the escape of 24 March 1944

It was only after the urns containing the actual remains of the fifty men arrived at the camp two weeks later that all lingering doubts were dispelled. The full story of the fate that befell the men eventually came to light. Hitler and the high command had first heard news of the escape while attending a conference at Berchtesgaden. Enraged, the Führer immediately demanded that all the escaped POWs should be executed once captured, though, with counseling from Göring and others, the number was finally revised down to fifty.

A secret communication known as the Sagan Order was circulated to all regional headquarters of the Gestapo and state police, the Kriminalpolizei or Kripo as it was more simply known. It stated that after capture and interrogation, fifty of the men were to be chosen and shot. A scenario was proposed wherein the POWs would be told they were being returned to the camp, only to be executed during a rest stop en route. All official reports would list that they were “shot while trying to escape.” Over the days that followed, all the escapees bar three were captured alive and imprisoned in various Gestapo or Kripo jails, where they underwent harsh interrogation. Ironically, Bushell and his partner had been the first to be recaptured.

In keeping with the Sagan Order chief of the Gestapo, SS-Gruppenführer Heinrich Muller ordered the head of Kripo SS-Gruppenführer Arthur Nebe, to select fifty from among the captured POWs to be be shot. Testimony given later at the Nuremberg Trials by another Gestapo officer, sheds more light on that dark moment in time.

“During one of these days at noon I received telegraphic instructions from General Nebe to proceed at once to Berlin to be informed of a secret order. When I arrived in Berlin that evening, I saw General Nebe in his office in Werdenscher Markt 5-7. I gave him a short, concise report on the whole matter and the way things stood at the moment. He then showed me a teletype order, signed by Dr. Kaltenbrunner, in which it was stated that, on the express personal order of the Füehrer, over half of the officers who had escaped from Sagan were to be shot after their recapture. The chief of Department 4, Gruppenfüehrer Muller, had received a similar order and would give instructions to the State Police. Military offices had been informed.”

Testimony – Obersturmbannführer Max Wielen – Nuremberg Trials, 1946

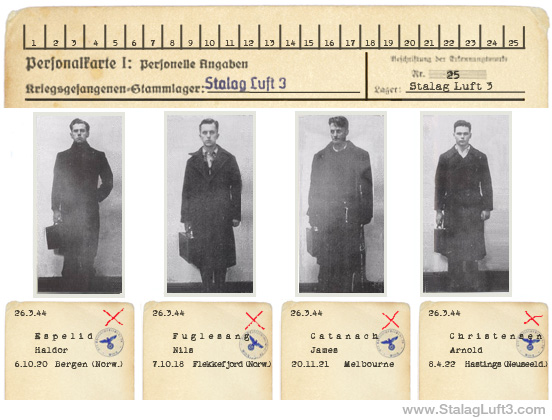

With the files of all the captured airmen on his desk, Nebe began the grisly task of creating two piles, one set marked with a fatal red X. Assisting him was Dr. Hans Mertens, who later graphically described the proceedings.

“I attributed Nebe’s excited and uncontrolled behaviour to the fact that he was aware of the monstrosity of the deed which he was about to carry out. There may have been six or eight perhaps even ten cards which I gave him. He threw several in front of me saying: ‘Have a look whether they have wives and children.’ After putting the cards which he had kept into two piles, he took my cards. I gave him briefly the personal particulars of these particular officers. I cannot remember the names of any. I remember however, that Nebe said in one case, ‘He’s for it.’ He put this card in one pile in front of him and looking at the picture of another officer said, ‘He’s so young, no.’ This card was put into another pile. On viewing another card he said, ‘Children, no’ and put it on the first stack. There were then several cards in both piles.”

Account – Dr. Hans Mertens

The files of the captured POWs with their fates sealed by a red X

Once the process was complete, the files of the ill-fated fifty were submitted to Müller who passed their names onto the various local Gestapo authorities responsible for the captured POWs. Throughout the first two weeks of March, those whose names had been selected were indeed lead to believe that they were returning to the camp, either alone or in pairs, though instead found only a bullet somewhere along the way. The Gestapo version of events reads like a carbon copy, with each prisoner shot while attempting to escape during a rest stop. In the case of Bushell, his death certificate was typed out several days before his killing. The remainder of the seventy-three captured were spared from the list and either returned to Stalag Luft III or separated into other camps. Only three men made it to freedom. Sgt Per Bergsland and P/O Jens Muller, two Norwegians, navigated their way to neutral Sweden, while F/L Bram van der Stok, a Dutchman, finally found sanctuary at a British consulate in Spain.

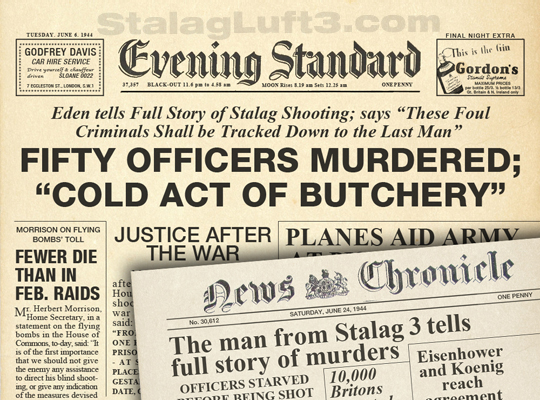

By May of that year, news of the atrocity had filtered back to England, after which British Foreign Minister, Anthony Eden, issued a robust speech to Parliament, promising that the perpetrators of the crime would be brought to “exemplary justice.” And indeed, as part of the post-war prosecutions in Germany, a special court in Hamburg meted out harsh justice to those most implicated in the murders.

British Press Reports, 1944

The dream for months of many, many men to which their hopes of happiness were bound. Twas built and found, destroyed and built again. This avenue to freedom underground!

The POWs were in due course allowed to construct a stone memorial to house the remains of ‘The Fifty’. It still stands to this day not far from the clearing in the woods that was once Stalag Luft III.

‘The sequel to this story must be told to show how fifty brave men died unseen….’